Yao Embroidery

The Yao, whose origins date back to southern China 2000 years ago, have their own unique beliefs based on a combination of animism, the belief in nature and ancestral spirits, and Taoism, which came from China. In ancient times, white cloth and thread had important significance in the Yao religion. They believed that white cloth was indispensable during rituals, and that the "embroidery threads" or "threads" could connect this world with the world of the soul and communicate their intentions.

Yao women are supposed to prepare wedding clothes for their mothers, mothers-in-law, and husbands within a year before their marriage. In the past when there was no contact with other villages or foothill societies, they would plant cotton, spin yarn, make dye with plants and trees, weave cloth, and embroider to make their clothes.

For women, embroidery was a way of arranging the "garments" of the family. Traditionally, they wore the same clothes every day, both when they were farming and when they slept, as they had no other clothes available. The women worked diligently on the farm during the day and had embroidery tools and materials constantly on hand to devote any free time they had to embroidery. It gave them pride to make and wear beautifully embroidered pants.

The head cloth that covers the head is just as important as the pants. From the time a baby is born, a hat is made and put on the baby to prevent ancestral spirits from taking it back to the other world and to protect the young child from evil spirits. In accordance with the ancient teaching that a girl's hair should not be shown to others, it was customary to replace the hat with a head cloth from the time the baby became a little girl. This headcloth is also embroidered. They embroider not only women's pants and headcloths, but also ritual and wedding costumes, children's clothes, and men's sashes.

We hardly ever see people wearing their ethnic clothing in their daily lives nowadays. On special occasions such as New Year's Day, weddings, and community events, however, women can be seen in splendid and bright traditional clothing. In the villages, you can also see elderly women wearing headdresses, which remind us of the people's desire to preserve their traditions.

Embroidery Patterns and Techniques

Yao embroidery patterns have been said to have special meaning in their daily lives and religion, but women today are embroidering without much regard to the meaning or names of the patterns. They seem to choose patterns simply because "it's beautiful" or "everyone else is doing it."

Some of the patterns have names such as tiger skin, tiger claw, silver flower, pumpkin flower, whirligig beetles, temple roof spires and many more. When you see the names of the patterns, you can assume that they are closely related to the daily life of the Yao. Around the age of eight, girls are taught the techniques by their grandmothers and mothers, and gradually acquire greater embroidery skills over time. Even though everyone has their own sample embroidery designs, the women know all the designs without any references and pass down their skill and knowledge orally from person to person.

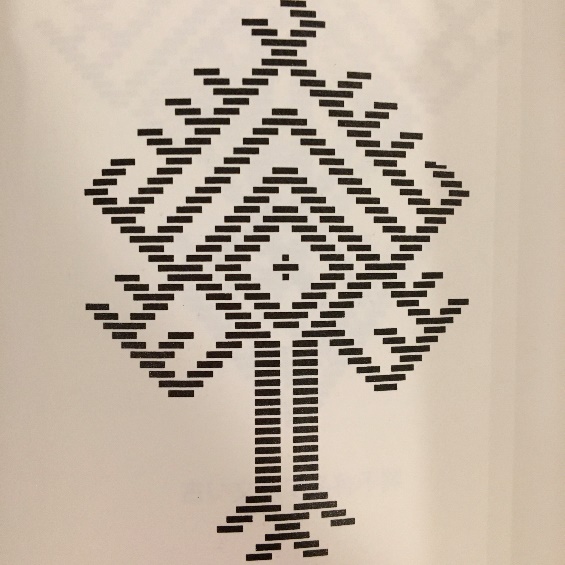

♦♦ Embroidery Stitches ♦♦- Weave Stitch

- This oldest method of stitching is to scoop out the cloth's base thread and stitch the pattern so that the embroidery threads are parallel to each other. There are few people who can do this nowadays.

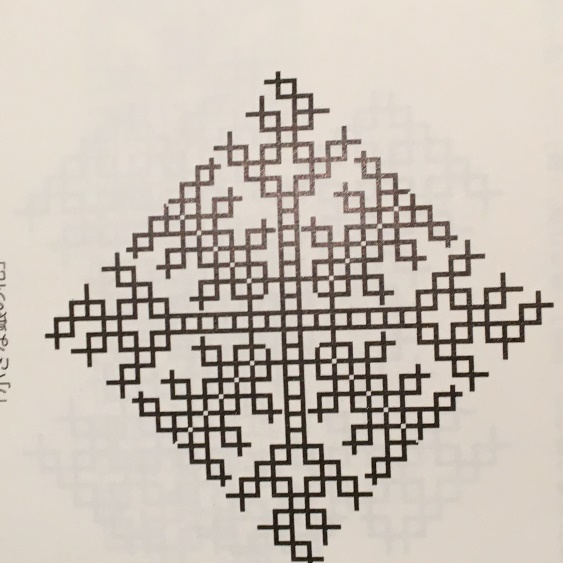

- Grid Stitch

- The stitching method is to create a lace-like pattern by scooping up the warp and the weft of the ground cloth. Only a few people can do this, too.

- *The technique of weaving stitches and lattice stitches is called "Laai Sawt" in Thai language

- Cross Stitch

- Cross stitch was used only for ceremonial cloth and was never used for women's pants due to severe restrictions. Nowadays, however, it is used instead of weaving stitch and lattice stitch because it looks gorgeous and is durable.

- Stem Stitch

- Used for straight lines to be inserted in the tiers and rows of the embroidery pattern. Usually, yellow, red and white threads are used.

Today, the women who remain in the Yao villages can embroider, but as more and more women leave their villages to work in cities or migrate, they gradually stop embroidering. Women in their 40s and 50s say that embroidery will end in their generation.

See LAO MIEN EMBROIDERY: Migration and Change by Ann Yarwood Goldman.